Belching is a physiological process, defined as the audible expulsion of air from the stomach or oesophagus into the pharynx (1). Although this is a normal bodily function, it can cause embarrassment in social situations, and when belching becomes excessive or is accompanied by other gastrointestinal symptoms, it can be highly intrusive and severely impact on patients’ quality of life.

The cause of excessive belching can be often attributed to lifestyle choices, gastrointestinal disease, behavioural causes or a combination of these factors. Determining the cause of excessive belching on an individual basis is important not only in treating this troublesome symptom, but also to help restore a better quality of life for the patient.

Belching can present in two different patterns, depending on the origin of the gas. “Gastric belching” is caused by gas venting from the stomach in association with a transient relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS). In contrast, “supragastric belching” (SGB) is caused by sucking air into the oesophagus, which is then quickly expelled as belch without crossing the LOS.

It is important to identify the cause of belching to help guide treatment, and this may not be clear on clinical assessment alone (2). Intraluminal impedance monitoring is imperative in determining the belching pattern and cause of this troublesome symptom.

Gastric belching can be identified on intraluminal impedance accompanied by high-resolution manometry (HRM-Z) as a retrograde movement of gas accompanied by relaxation of the LOS and upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) (Figure 1b). Frequent or excessive gastric belching can be identified and quantified using 24-hour ambulatory intra-luminal multichannel pH/impedance monitoring (Figure 1a).

Figure 1a – Gastric belch characterised by relaxation of both LOS and UOS and high impedance moving in the retrograde direction as shown by HRM-Z. Figure 1b – Gastric belch as measured by 24-hour ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring, characterised by the increase in impedance in the retrograde direction.

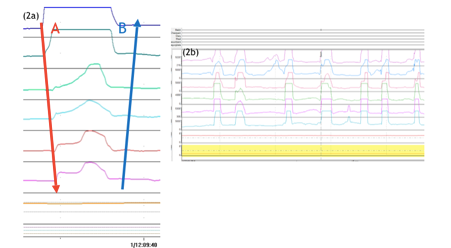

SGB has a distinct waveform identifiable using 24-hour ambulatory pH/impedance monitoring. Impedance first increases in the antegrade direction as air is sucked into the oesophagus from the pharynx. When is it quickly expelled from the oesophagus this causes the impedance to increase in the retrograde direction (Figure 2a). SGB can occur as isolated episodes or prolonged supragastric ‘attacks’ (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a (left) – SGB identifiable on 24 hours pH/impedance monitoring, characterised by sucking in air (A) and expelling it quickly from the oesophagus (B). Figure 2b (above) – repetitive SGB.

Behavioural Causes

Aerophagia is a behavioural condition where excessive air swallowing can lead to symptoms of bloating and distension. When aerophagia is accompanied by the primary symptom of belching, this is considered excessive belching (3). This may occur when the anti-reflux barrier is compromised and instead of swallowed air being trapped in the abdomen, contributing to distension, it breaches the LOS as a belch. These increased number of transient relaxations of the LOS may increase levels of gastroesophageal reflux. There is evidence to show that patients with functional dyspepsia have a significantly greater number of air swallows and gastric belches than healthy controls (4).

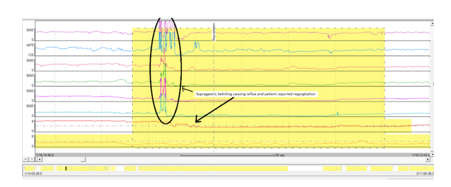

Utilising ambulatory impedance monitoring to identify aerophagia and educating patients on this behaviour may be the first step in reducing these events. Lifestyle modifications such as taking time when eating meals, avoiding fizzy drinks and ceasing chewing gum may reduce the volume of air swallowed. High frequency of SGB (>13 episodes in 24 hours) is also associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Research has shown SGB often precede reflux episodes, with sudden changes in the abdominal/thoracic pressure gradient driving gastric contents into the oesophagus (Figure 3).

Supragastric driven reflux accounts for up to 1/3 of total oesophageal acid exposure in some reflux patients (5).

With an estimated 3.4% of tertiary referrals for upper GI complaints expressing pathological SGB (3), correcting this behaviour may resolve reflux symptoms in this subset of patients. Patients with pathological SGB may also present with rumination type symptoms or initiate this behaviour following anti-reflux surgery (6,7).

Figure 3– Acidic reflux episode and patient-reported regurgitation preceded by SGB.

Why patients supragastric belch is somewhat unclear, however, it is thought to begin as a voluntary action to relieve discomfort, which in time becomes subconscious (8). Stress is also thought to exacerbate the frequency of SGB (9).

There is limited evidence for medical therapy for SGB. One trial demonstrated the efficacy of baclofen in the treatment of SGB and rumination, reducing both symptoms and postprandial flow events (10). A further case study provided evidence to demonstrated a 90% reduction in SGB events using a combination of baclofen and pregabalin (11).

Speech therapy centred around making the patient aware of their behaviour is efficacious in reducing SGB (12). Cognitive behavioural therapy has also been shown to significantly reduce belching, acid exposure time and improve quality of life in patients with pathological SGB (13).

Gastrointestinal Disease

When excessive belching shown by impedance is not accompanied by excessive air swallowing or SGB, investigations to evaluate small bowel disease may be useful. In small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), over proliferation of microflora in the small bowel can lead to premature fermentation of ingested food and drink. Waste products of this fermentation include water, short chain fatty acids and gases. Production of these waste products can induce symptoms of bloating, abdominal discomfort, belching, flatulence and altered bowel habit. A non-invasive hydrogen/methane breath testing can be utilised to test for SIBO. In the case of a positive diagnosis, treating SIBO with antibiotic therapy may reduce belching.

To Conclude

Excessive belching may often present as a primary complaint or be associated with other gastrointestinal symptoms. Physiological testing is key in determining the aetiology of belching on an individual patient basis. Addressing the underlying belching mechanism or cause may help relieve other gastrointestinal symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life.

References:

- Disney B, Trudgill N. Managing a patient with excessive belching. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2014;5(2):79-83. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2013-100355.

- Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1466–1479.

- Bredenoord, Albert J. Management of Belching, Hiccups, and Aerophagia. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology , 2013;11:6 –12.

- Conchillo JM, Selimah M, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Air swallowing, belching, acid and non- acid reflux in patients with functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 965–971.

- Koukias N, Woodland P, Yazaki E et al. Supragastric belching: prevalence and association with gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophageal hypomotility. J. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;21:398–403.

- Tucker E, Knowles K, Wright J et al. Rumination variations: aetiology and classification of abnormal behavioural responses to digestive symptoms based on high-resolution manometry studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:263–274.

- Broeders JAJL, Bredenoord AJ, Hazebroek EJ et al. Effects of anti-reflux surgery on weakly acidic reflux and belching [Internet]. Gut 2011;60:435–441.

- Hemmink GJM, Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL a M et al. Supragastric belching in patients with reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1992–1997.

- Bredenoord AJ, BLAM Weusten, Timmer R et al. Psychological factors affect the frequency of belching in patients with aerophagia. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2777–2781.

- Blondeau K, Boecxstaens V, Rommel N et al. Baclofen improves symptoms and reduces postprandial flow events in patients with rumination and supragastric belching [Internet]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:379–384.

- Kunte H. Successful treatment of excessive supragastric belching by combination of pregabalin and baclofen. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015;69:124.

- Hemmink GJ, Ten Cate L, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Speech therapy in patients with excessive supragastric belching—a pilot study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22: 24–28, e2–3.

- Glasinovic E, Wynter E, Arguero J et al.(2018). Treatment of supragastric belching with cognitive behavioral therapy improves quality of life and reduces acid gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 10.1038/ajg.2018.15