Stomach acid plays two important roles in your body: breaking down food and killing harmful microbes that you ingest1.

Acidity levels are measured by the pH scale from 1 to 14, with 1 being the most acidic, 7 being neutral, and 14 being the most alkaline.

The pH of stomach acid (hydrochloric acid) is around pH 1, which is as strong as battery acid. Although, gastric juice also contains water and mucus, so normal pH of the stomach is typically between pH 1.5 to pH 3.5,

Low stomach acid, also known medically as hypochlorhydria, is when the stomach does not produce enough acid to maintain a strong acidic environment.

Complete loss of stomach acid production is called achlorhydria.

It is also possible for the stomach to produce too much stomach acid. This is usually caused by the condition called Zollinger-ellison syndrome, where the body produces excess gastrin, the hormone required for stomach acid production2.

What causes low stomach acid?

The most common causes of low stomach acid (hypochlorhydria) are:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) – medications used for the treatment of heartburn and acid reflux that work by blocking stomach acid production e.g. omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, etc3.

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) – a type of bacteria which survives in the stomach by secreting an enzyme that neutralises stomach acid. H. pylori infection causes gastritis, which leads to less stomach acid production4.

- Autoimmune gastritis – an autoimmune disease where the immune system destroys the acid producing cells in the stomach called parietal cells5. This can also lead to vitamin B12 deficiency, or pernicious anaemia.

- Thyroid issues – low stomach acid is common in both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Also, stomach acid is needed for the absorption of the thyroid medication, l-thyroxine6.

What are the symptoms of low stomach acid?

The most common symptoms of low stomach acid are discomfort in the stomach, bloating, belching and a feeling full quickly or feeling full for long periods after eating.

Low stomach acid may lead to poorer digestion of proteins because pepsin, the digestive enzyme which breaks down protein, is most active in acid at around pH 2.

Having low stomach acid puts you at an increased risk of intestinal infections like bacterial gastroenteritis (food poisoning) and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

SIBO is characterised by symptoms of bloating, abdominal pain, and nausea due to excess gas produced by bacteria in the small bowel7. The Functional Gut Clinic can test for SIBO using simple, at home breath test kits.

Despite online claims, there is no evidence that low stomach acid causes reflux. The treatment for acid reflux and heartburn is PPIs, which lead to low stomach acid. People who have been taking PPIs for 6-months or longer are more likely to have troublesome bloating and SIBO8.

How to test for low stomach acid?

Symptoms of low stomach acid, such as bloating, fullness and nausea, overlap with many other conditions, such as functional dyspepsia, gastroparesis, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Therefore, symptoms alone cannot diagnose low stomach acid.

To diagnose low stomach acid, you need to measure gastric acid output. To do this, a capsule or probe with a pH sensor is placed into the stomach. Then a standardised meal is given, such as a nutrient drink. This will buffer the acid levels in the stomach. Then we time how long it takes for your stomach to reacidify after the meal.

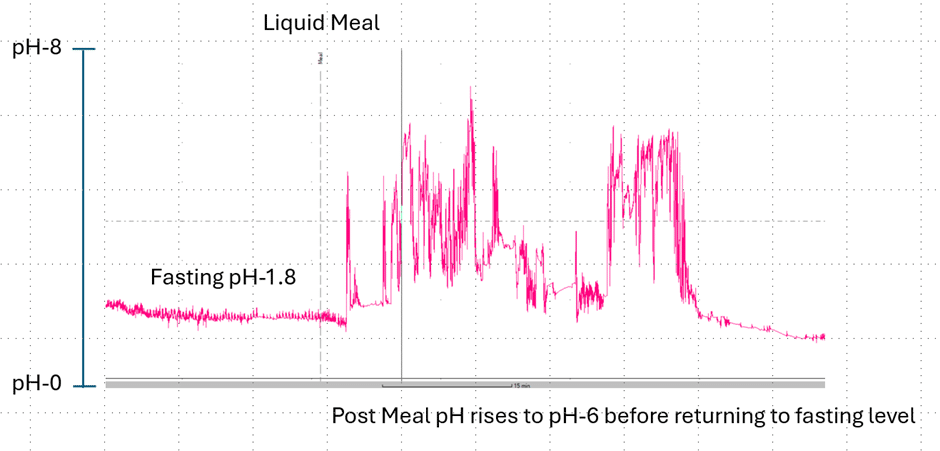

Here is an example of a normal and abnormal gastric acid output study:

This image shows a normal gastric acid output test. At the beginning of the study the pH probe is placed via the nose into the stomach and we record the fasting gastric ph which in this case is around pH-1.8 which is normal. We then give the nutrient drink which ‘buffers’ the gastric acid so the pH rises to around pH-6. The stomach then responds by secreting more acid and as the drink empties out of the stomach the pH returns to it’s normal fasting levels. This normally takes around 35-40-minutes and by measuring the pH and the timings we can calculate the gastric acid output levels very accurately in units called milliequivalents per minute (mEq/min).

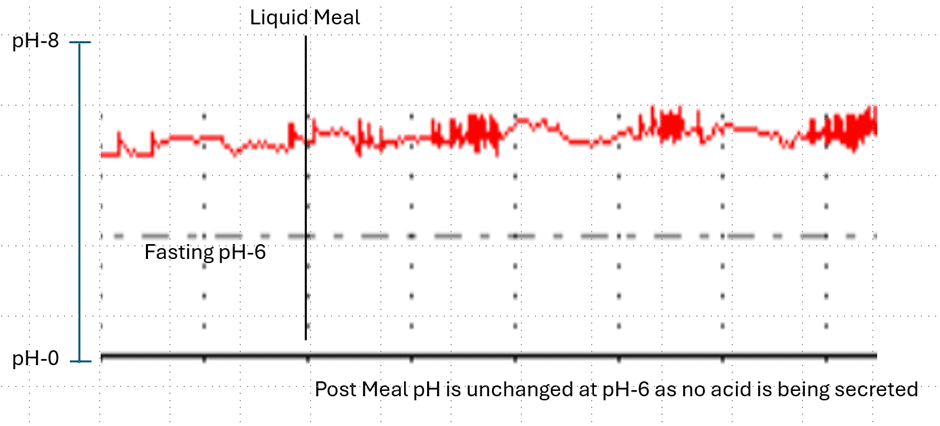

This second image shows the same response in a person with achlorhydria (no stomach acid production).

Here it can be seen that the fasting gastric pH is around pH-6 so no evidence of normal acid production. When we give the test meal the pH doesn’t change as the parietal cells in the stomach no longer function, this obviously causes problems with normal gastric digestive process so the question is can we treat this?

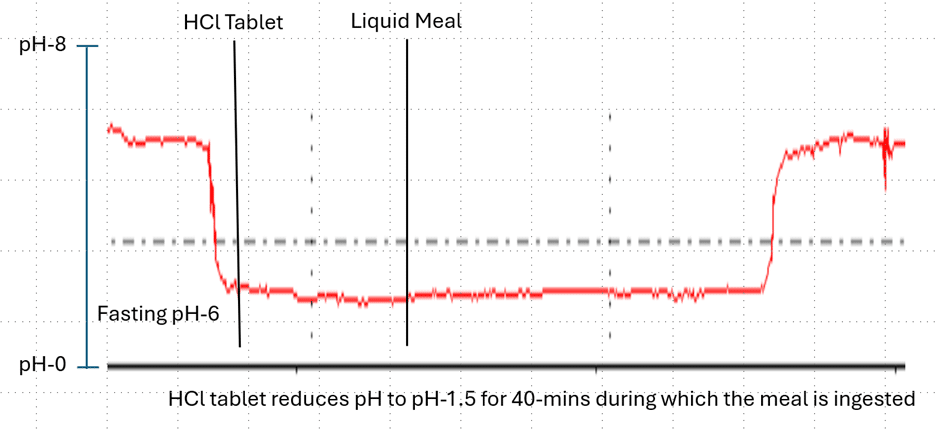

Whilst we can’t restore normal parietal cell function, we can use hydrochloric acid (HCl) tablets that also contain the enzyme pepsin to help mimic the conditions under which normal gastric digestive process occur. In this next image, we show the effect of taking these tablets in a patients with achlorhydria.

This image shows once again an abnormal fasting pH of around pH-6. This time the patients takes 2 x 600mg HCl +pepsin tablets commonly available from pharmacies. It can be seen that the tablets reduce the gastric pH to around pH-1.5 consistent with what would occur normally in an unaffected stomach. The pH remains low for around 40-minutes during which the patient had a ‘normal’ meal having the benefit of a normal gastric digestive environment. During the gastric acid output test we can test these treatments to see what dose may be best for each individual.

Are there any other ways to test low stomach acid?

The baking soda test for low stomach acid has no evidence to show it works. The theory is that baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) will react with stomach acid (hydrochloric acid) to produce gas (carbon dioxide) which will be belched. However, this may lead to a false positive or false negative diagnosis, especially since most belches are caused by how much air you swallow whilst drinking.

Are there an other ways to treat low stomach acid?

Apple cider vinegar (ACV) is claimed to be helpful since ACV has a similar pH to stomach acid of around 2.5. However, ACV does have proven side effects including

The most effective way of treating low stomach acid is to treat the underlying cause of low stomach acid. For example, stomach acid levels may return to normal after eradicating H. pylori infection.

Stopping PPIs will allow stomach acid levels to return to normal. If you are unsure whether you need PPIs, then it is important to consider testing for acid reflux complications, such as Barrett’s oesophagus, because these medications prevent damage to the oesophagus from acid, which if untreated, may increase your risk of oesophageal cancer10.

In conclusion, low stomach acid may lead to nutrient deficiencies and increased risk of intestinal infections and SIBO, due to stomach acid’s roles in digestion and killing microbes.

The good news is that low stomach acid can be diagnosed with a gastric acid output test, and helping the gastric digestive environment with HCL and pepsin tablets are limited to treating the underlying cause.

There is a lot of misinformation on the internet about low stomach acid, meaning that it can be easy blame to it as the cause of many health problems. For more information about testing for low stomach acid go to:

References

- Hunt, R.H., Camilleri, M., Crowe, S.E., El-Omar, E.M., Fox, J.G., Kuipers, E.J., Malfertheiner, P., McColl, K.E.L., Pritchard, D.M., Rugge, M., Sonnenberg, A., Sugano, K. and Tack, J. (2015). The stomach in health and disease. Gut, 64(10): 1650-1668

- Lee, L., Ramos-Alvarez, I., Ito, T. and Jensen, R.T. (2019). Insights into effects/risks of chronic hypergastrinemia and lifelong PPI treatment in man based on studies of patients with Zollinger-ellison syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(20): 5128

- Neumann, W.L., Coss, E., Rugge, M. and Genta, R.M. (2013). Autoimmune atrophic gastritis- pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 10(9): 529-541

- Waldum, H.L., Kleveland, P.M. and Sordal, O.F. (2016). Helicobacteri Pylori and gastric acid: an intimate and reciprocal relationship, 9(6): 836-844

- Virili, C., Bruno, G., Santaguida, M.G. et al. (2022). Levothyroxine treatment and gastric juice pH in humans: the proof of concept. Endocrine 77, 102–11

- Pimentel, M., Saad, R.J., Long, M.D., Rao, S.S.C (2020). ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(2): 165-178

- Su T, Lai S, Lee A, He X, Chen S. Meta-analysis: proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J Gastroenterol. 2018 Jan;53(1):27-36

- Peloso, E. (2016). Apple cider vinegar for diabetes: Limited evidence, potential risks. Pharmacy today, 22(2): 18

- Yago, M.A.R., Frymoyer, A.R., Smelick, G.S., Frassetto, L.A., Budha, N.R., Ware, J.A. and Benet, L.Z. (2014). Gastric Re-acidification with Betaine HCl in Healthy Volunteers with Rabrazole-Induced Hypochlorhydria. Molecular pharmaceutics, 10(11): 4032-4037

- Jankowski JAZ, de Caestecker J, Love SB et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): a randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2018;392:400–8.