Barretts Oesophagus: Everything You Need to Know About

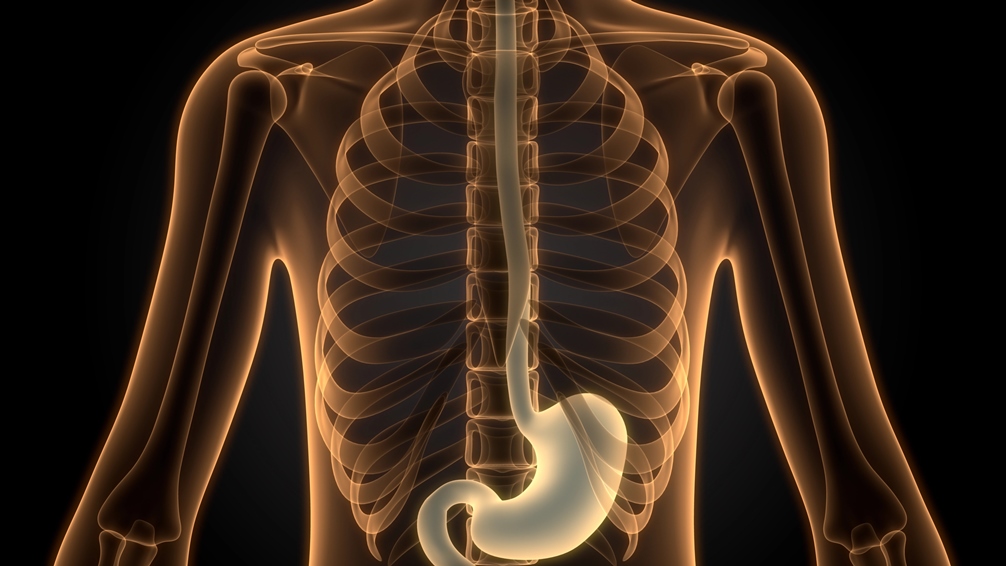

Repeated acid attacks due to reflux can damage your oesophagus (food pipe). Over time, the cells lining your oesophagus begin to change, becoming more like your stomach. This is known as Barrett’s oesophagus.

These cellular changes only occur after persistent acid reflux and acid exposure often causing chronic heartburn symptoms. This is associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

While the condition isn’t immediately severe, it can increase the risk of cancer. Understanding Barrett’s oesophagus — including what it is, its symptoms, causes, and diagnosis and management — is crucial for preventing its progression.

What Is Barrett’s Oesophagus?

Barrett’s oesophagus is a condition where the flat pink lining of the oesophagus — the tube that connects your mouth to your stomach — becomes thickened and red due to damage from acid reflux.

Usually, the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), between the stomach and oesophagus, prevents the backflow of acid. However, if this becomes weakened or the pressure in the stomach is too high, acid can move backward. Repeated acid attacks are known as GERD.

Gradually, the acid begins to alter the oesophageal lining, triggering a change in cells. These cells are trying to adapt to the constant presence of acid.

Barrett’s oesophagus is linked to a higher risk of oesophageal cancer. This risk is small but notable and requires continuous monitoring.

Symptoms of Barrett’s Oesophagus

Most people with Barrett’s oesophagus will experience prolonged heartburn. Rarely, people may have silent reflux, where acid reflux occurs without symptoms.

Look for these symptoms:

Persistent heartburn or acid reflux

Difficulty or pain when swallowing (dysphagia)

Chest discomfort or burning sensation

Regurgitation of food or sour liquid

Chronic cough or hoarseness (especially at night)

Around half of people with Barrett’s oesophagus experience little to no acid reflux symptoms. Despite sounding strange, it makes sense. People who experience repeated heartburn are more likely to change their lifestyle or seek treatment, preventing the worst outcomes.

Causes of Barrett’s Oesophagus

The causes of Barrett’s oesophagus aren’t complicated. It exclusively occurs due to repeated acid exposure. The causes include:

Chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) — long-term acid reflux is the main cause

Frequent acid exposure damages the oesophageal lining over time

However, the underlying triggers behind the reflux can vary. Some common risk factors include:

Hiatus hernias, which increases reflux risk

Obesity, especially around the abdomen

Smoking

Older age (most common in adults over 50)

Male sex (men are more frequently affected)

Family history of Barrett’s oesophagus or oesophageal cancer

Diagnosing Barrett’s Oesophagus

Barrett’s oesophagus cannot be diagnosed solely from medical history. Nor is it measurable on a blood test. Your doctor will need to perform an endoscopy to visualise the cellular changes in your oesophagus, often with biopsies taken.

A thin tube with a camera and light at the end (endoscope) is threaded down your throat. The doctor will inspect the oesophagus. The normal lining is pale and glassy, whereas Barrett’s oesophagus appears red and velvety.

A tissue sample (a biopsy) is often taken for further analysis. The tissue can be categorised into three groups:

No dysplasia: Barrett’s oesophagus is present, but the cells look normal with no signs of precancerous change.

Low-grade dysplasia: Some early, mild precancerous changes are seen in the cells.

High-grade dysplasia: More advanced changes are present. This stage is considered the final step before oesophageal cancer can develop.

Who Should Be Screened for Barrett’s Oesophagus?

Most people do not require screening for Barrett’s oesophagus — even if they have GERD symptoms. It is recommended for men who have persistent GERD symptoms that fail to respond to treatment, plus two or more risk factors:

Having a family history of Barrett’s oesophagus or oesophageal cancer

Being male

Being white

Being over the age of 50

A current or past smoker

Carrying excess abdominal fat (central obesity)

Women may also require screening for uncontrolled reflux if they have some of the above risk factors. The determination is up to your doctor.

Management and Treatment of Barrett’s Oesophagus

Treatment for Barrett’s oesophagus depends on the level of abnormal cell growth. If there is no dysplasia, then management involves a periodic endoscopy to monitor for further cellular changes and normal GERD treatment (e.g., acid reflux medications and lifestyle changes).

If there is low-grade dysplasia, e.g., precancerous changes, the treatment is more intensive. Your doctor may recommend:

Watchful waiting — another endoscopy in six months, with continual follow-ups.

Endoscopic resection, where the damaged cells are removed.

Radiofrequency ablation, which uses heat to remove abnormal tissue.

Cryotherapy, which uses cold liquid or gas to damage the abnormal cells.

If the dysplasia is high-grade, your doctor (or surgeon) may recommend the same treatments listed above. However, they may opt to remove the damaged section of the oesophagus entirely due to the risk of cancer.

Get Checked for Barrett’s Oesophagus or Reflux Damage

If you’ve had long-term heartburn or acid reflux, it’s important to understand what’s really happening inside your oesophagus.

The Functional Gut Clinic offers specialist testing, including Endosign capsule sponge test, pH monitoring, and oesophageal manometry, to assess acid exposure, functioning of the oesophagus and potential detection of early signs of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Book your heartburn and reflux assessment today. Early diagnosis saves lives and prevents severe illness.